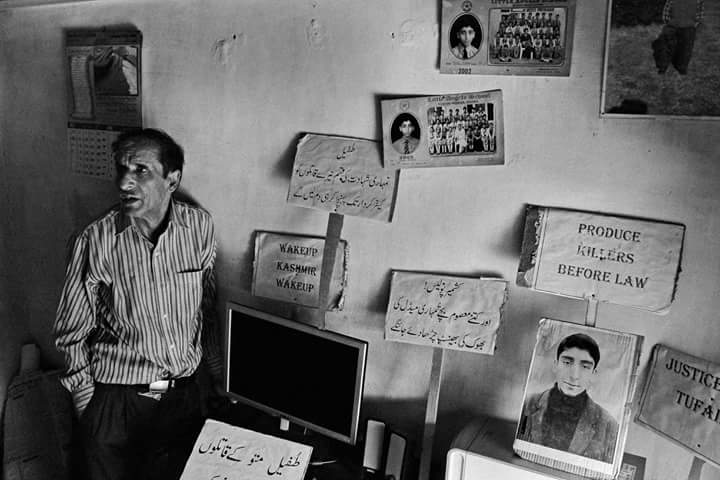

Father of slain Tufail Mattoo continues to fight the case. Pic source; internet

Tufail Matoo, a teenage student was killed on this day, July 11, 2010 in old city Srinagar. He was coming from tuitions when he was hit by a tear gas canister fired allegedly by the police.

The incident happened when police was dispersing the pro-freedom protesters who were demanding that a probe should be held to investigate the killings of three Kashmiri boys by the army on the Line of Control in Keran sector.

Later, it turned out to be three boys were locals and were killed by the army in a staged encounter. The media reported that army punished seven soldiers for staging the encounter, but till date, Tufail’s father, Ashraf Matoo, is fighting for justice. The police have told the court they were unable to locate the policeman who fired the tear gas canister.

The killing of Tufail Matoo triggered widespread anger and pro-freedom protests across Kashmir in 2010. The pro-freedom uprising, termed by the foreign press as Kashmir intifada, witnessed the killing of over 130 civilians, not to speak of countless injuries

Journalist Wasim Khalid wrote this report on the day Tufail Matoo was killed. He recounts that how he and his other journalist colleague were the first to inform the family that Tufail was dead. Here we reproduce the first person chilling account on Tufail’s death anniversary;

In Kashmir’s traditional households, people walk brisk feet to open the door when a guest knocks. Here, a visitor is like good news. Showkat Matoo might have been expecting no less when he came out in his casuals – a loose white T-shirt and pajamas – and smiled at us while opening that gate.

Greetings were exchanged between bewilderment gathering in the form of sweat on my face. As I exchanged a look with my friend, we realized we had news few would want to deliver.

“Does Tufail Matoo live here?” my friend asked reluctantly. Before Matoo could answer, my friend found the strength to add, “Who was killed at Rajouri Kadal, half an hour ago.”

Matoo fell silent for a moment, thinking.

“I am not aware about any killing,” he said, floundering. “Tufail lives here. I am his uncle. He had left home for maths tuitions”.

I remained silent all this while. My friend kept talking about the Rajouri Kadal incident with him. It was a paradox. We had come to get details about the boy for a news story in my paper. Here, we had to decide what to tell the family about Tufail. We were not even sure whether we had landed at the right door. And if we did, why was it us that should deliver the news of the death? But it seemed too late.

“Why are you looking for Tufail?” he questioned again.

“We heard something happened to a person with the name Tufail at Rajouri Kadal,” my friend told him. “We were looking for his house”.

He grew pale and nervous. And he retraced his steps back into the house.

My friend, a tall well built man, sat down on his haunches. An expression of pain flitted through his face. “I informed him about Tufail. We don’t know whether he is the same one,” he told me in a weak voice. Sweat rolled down my back too. I became restless.

After a brief interval we heard a loud wail. More wailing and two girls rushed out of the house, stood on a patio, tears bursting, screaming. “Who will bring our Tufail back.”

As the wails made their way through the streets to other houses, men started gathering on the dusty street outside the house. Few family members, especially males, rushed outside to confirm the death from us. Two persons standing near the gate raised doubts. “It may not be the same Tufail,” one of them said. Another neighbour, in a brown khan suit said he saw Tufail just half an hour ago. More people stopped at the gate. Someone remarked that the boy who died might be from another locality. No one wanted to accept that Tufail, there boy from the locality, could have been killed at Rahouri Kadal. No one wished him dead.

A painting depicting the dead body of Tufail Mattoo. Pic source internet

People’s suspicion raised hopes for the family that Tufail was alive. Someone told the women and wailing stopped. But silence ruled the house. The family members began enquiring about his well being. They telephoned his friends, relatives, distant cousins. The pursuit continued.

Two an hour and a half earlier, exactly at 6:00 pm, I had received a phone call.

“A boy has been shot dead at Rajouri Kadal,” a reporter friend told me. Instantly, I asked Nasrun – my colleague – to accompany me. We hurtled on a bike towards the place where the boy was killed – Ghani Memorial stadium.

The protesters had blocked all the roads leading to Ghani Memorial Stadium near Safakadal, a neighbouring locality. Troops were deployed in large numbers – Central Reserve Police Force personnel in riot control gear and police personnel, equipped with bamboo sticks and tear smoke guns were chasing away the protesters into narrow alleys.

It was impossible for us to make way through the riot to reach the stadium. I asked Nasrun to turn around and take me to the victim’s house. “His name is Tufail Ahmad Matoo. He was killed after he was hit by a stone in head. His father’s name is Mohammad Aziz Matoo. The victim belonged to Saidakadal,” a police official from Police control room told me on phone.

We looked for the shortest possible route. A man standing near a shop at Safakadal chowk pointed towards a narrow lane. My friend, Nasrun negotiated with protesting crowds and sharp blind curves of narrow lanes of old Srinagar to reach Saidakadal.

We were dazed on arriving there. There was no commotion, no protests, not a single trace of mourning characteristic of Kashmir conflict when somebody gets killed by Indian troops.

Nasrun left for home, leaving me there to find out.

In the meanwhile, two more friends arrived and joined me in the pursuit of the victim’s house. Mudasir, a reporter friend, and I began enquiring from bystanders, shopkeepers and vegetable vendors – no one had clue about any death in the neighbourhood.

At last we reached a shop opposite to the Sikh holy place, Chattipashai. A visibly decrepit, low lit shop sold traditional earthen ware, tobacco and candies. Owner of the shop, an old man who wore a white cropped beard, sat contently on a small blanket laid on the cemented floor. He took long drags from his cigarette as he listened to the gossip of other people surrounding him.

Mudasir interrupted the gathering. “Do you know anybody with name Tufail Ahmad Matoo?” he asked. The shopkeeper pointed towards a red three-storied house. Everything appeared so normal.

“I do not want to inform the family,” I told Mudasir.

“Let us go there,” he replied. “They would anyway come to know about it.”

It was already past 7:30 pm now. The family was yet to know where Tufail was. The search continued. A street, deserted till moments ago, was now noisy. People chatted in small groups. Others made phone calls. Everyone talked about Tufail, the possibility of his death recalling incidents in the past. They talked of possibility of the impossible in occupation and the attitude of the troops and local police.

Tufail’s uncle kept calling people. He telephoned local police station, but did not get any specific details. Relatives and neighbours came to us again to know what we had known. “The Police Control Room (PCR) informed us about Tufail. They said his body was lying in the mortuary there,” I informed them.

Soon, Tufail’s uncle and other men from the family were headed to the Police Control Room.

As if my body had lost all energy, my legs began to pain. It has never been easy to see people die, no less easier seeing the families wail and mourn their dead, fathers carry their sons’ coffins and bury them young. I sat on a pedestal of the wall bordering Tufail’s house. Mudasir walked a little away and stood near Tufail’s neighbours house. The other friend, who had informed the family, kept talking to people.

I noticed a plaque fitted in the boundary wall of Tufail’s house. It had Khaleel Mansion inscribed in golden words. I looked back towards the house carefully. I journeyed back to my old house. There was a striking resemblance between Tufail’s and my residence. The architecture, the façade design, the white paint covering mortar between bricks, the bricks walls painted in red, the railings and the courtyard.

For a while, it seemed as if the tragedy had befallen on my family. I could share the pain. It felt like somebody had pricked my heart with a needle and had made my spines tingle. Tears beaded in my eyes. I held my emotions back. “I can’t not be so weak,” I thought.

Around 9 pm, the men returned. It was confirmed that the boy killed at Rajouri Kadal was Tufail Ahmad Matoo from this house.

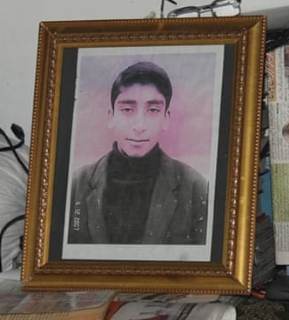

A photographic frame of Tufail Matoo. pic sources: Internet

By now the evening had melted into darkness of night. Orange lights illuminated the streets. The crowd outside the house had swelled into hundreds, may be thousands. The wailing was punctuated with pro-freedom slogans.

Covering deaths and destruction in Kashmir, I never thought that we would one day become messengers of death – that we would be the first to “break the news” to a family about their son’s murder. I was cursing myself, my job. I asked myself “why we?”

Tufail was 17. His father, Mohammad Ashraf Matoo, worked in Bombay and also had a shop in Gulf. The relatives said Tufail’s body was still lying in the Police Control Room. They said police refused to hand over it fearing large scale protests.

As the word of his killing spread, the relatives started arriving. Every relative, who entered that black gate, was awe-struck and screaming. I remember a woman, who had rubbed turmeric on her forehead, and was beating her chest persistently.

The entire area had plunged into grief. Everyone mourned in despair, helplessness. Their loss was irreparable. An instant feeling of being enslaved became evident on each face.

I desperately longed to see Tufail. I started looking for his photograph. I talked to his relatives, friends and neighbours asking them to arrange a single picture. Nobody was able to provide one.

Tufail Matoo’s school group picture. pic source: internet

I saw Tufail’s father. As if he ceased to exist. He had cupped his face in right hand. His downcast eyes fixed were on ground. I felt he was thinking about Tufail – his lone child.

Tufail’s mother was out of her wits. She would walk barefoot up to the gate, waited for some moments outside it, looked both ways in the street, and then returned back to the patio. She would repeat it again and again.

“He had gone for tuitions,” she cried while tears bursting in her eyes. “Why my son has not arrived? It is too late. He used to arrive home beforethe sunset.”

She would approach Tufail’s grieving father, insisting him to go and look for her son. He only reply was silence. She continued to do it till we left…

In pursuit to know what actually happened to Tufail, I began asking people. I talked to small groups of mourners outside the house. I met Tufail’s neighbour, who runs a shop at Rajouri Kadal. He happened to be an eyewitness and narrated me the whole story.

He said the incident happened at around 5:30 pm when police resorted to cane charging and indiscriminate firing near Gani memorial stadium. “There were no protests except some stray stone throwing in Rajouri Kadal area,” a shopkeeper, who wished not be named, said. “Shops were open and traffic was plying as usual.”

He said batches of students, with bags hung on their shoulders, were walking on the road after finishing their tuitions.

“The police and CRPF personnel aboard vehicles came from Kawdara neighbourhood and started chasing few protesters,” he said. Sensing trouble,the bystanders and students had begun to run for safety. “But more police vehicles come from the opposite direction in a bid to trap them. Shoppers and students ran towards Ghani memorial stadium. We started closing our shops,” he said. “It gave people a chance to cross over to a safer zone. However, the police resorted to beating, they fired tear smoke canisters and bullets inside the stadium as people were running.”

He said that panic gripped people who had been running to safety. Policemen, he said, “targeted” Tufail by shooting him from a close range in his head inside the stadium.

“He fell there, blood gushed out of his head, and he died,” the shopkeeper said. “His brain spattered the grass on the playfield.”

Tufail’s maternal uncle, standing next to us with the grieving circle of relatives, was listening to shopkeepers’ story carefully. He broke down. Theuncle showed us a picture of tattered brain on his mobile phone. “A boy transferred this image on my mobile phone. He told me it was a brain of some person killed near Ghani memorial stadium,” he said as tears welled up. “I did not know he was my Tufail. Oh Allah, have mercy on us.”

Relatives of Tufail Matoo gather around his grave. Picture source: internet

When we left Saidakadal, the police had laid restrictions on movement on the streets. Reinforcements were rushed to the area to prevent the “law and order” situation from worsening. Police buses were rushing past us.

On the other side, young boys were demonstrating their anger. “We want freedom,” they shouted. “Go India Go Back.”

I reached my office by 10:30 pm.

I wanted to have a look at Tufail’s photo. There was a picture shot by our photographer. It contained the tattered brain spread over a piece of newspaper and green grass. A five rupee coin also figured. Tufail was not to be seen in the picture.

The other photo, which was provided by police, showed Tufail laid in a mortuary. The right portion of his head was ripped open. The right eye was hidden under flesh and the head was drenched in blood. I did not want to see any more.

While writing the story, I found three contradicting statements regarding Tufail’s killing issued by police. In first statement, police said Tufail was killed after hit by a stone. The statement was seconded by another one saying, “The killing seems to be a case of murder”. They further said police is on the look out of two people who brought him to hospital in Maruti car.

Both the statements were retracted afterwards. The police said they are investigating how and why Tufail was killed?

For police, Tufail’s killing was just a mere statistic, but for a family, the loss was irreparable. And for an ordinary Kashmiri, he was a symbol of resistance, who died with the bullet fired by “occupation forces”.

That night, as I reached home at midnight, thoughts of Tufail’s killing and lingered in my mind. I thought about the weeping mother and thetraumatized father. The image of tattered brain and flesh refused to go away. I wondered about that 5 rupee coin. Why was it there? I could not sleep. Since then, there have been many sleepless nights.